Damage to industrial equipment is commonplace and the costs of repairs can be massive, depending on the size of the equipment. In order to restore the equipment’s capabilities, following damage that compromises the structural integrity of the metal element, certain repair methods have been traditionally favoured. However, advancements in technology have changed the way in which original operating conditions can be restored, whilst keeping in line with current health and safety standards. Throughout this post, we discuss the benefits of cold bonding versus the traditional hot work option of welding.

New era of repair technology

Amongst metal equipment structural repair, welding is a recognised hot work repair method that is practised worldwide. Despite this knowledge having existed for a long time, asset owners have recently been searching for faster and safer methods of obtaining an effective repair. Hot work required for welding, grinding and cutting operations all present potential hazards when conducted in potentially explosive and flammable environments. In order to minimise the risk, cold bonding techniques involving materials that are applied and cure at ambient temperatures can offer an alternative solution for repair and new build applications on metallic surfaces.

The stresses of hot work

The reason owners are looking elsewhere is because these welded repairs often cause problems later on in the equipment’s service life, as a result of both the process and the limitations of welding. The most common problems associated with this form of hot work include:

- Changing of the substrate microstructure due to application of heat

- Cavities behind weld patches and brackets

- Bi-metallic corrosion

- Existing heat sensitive coatings/linings

Assessment of the risks required before carrying out any hot work makes welding a highly time consuming process and therefore safer and time saving alternative options are becoming popular among the industry professionals. In scenarios of flammable and explosive environments, the welding process is restricted, since sparks and hot metal can fly off in all directions and may drop down, creating hazardous situations.

Fundamentally, the weld itself can cause distortion of the substrate, due to heat. More commonly known as HAZ (Heat Affected Zones), the intense process of heating and subsequent cooling of the substrate can generate weaknesses in the metal and limit the structural integrity at the weld point. In certain applications the metal must undergo stress relief to ensure that the risk of subsequent changes to the metal is minimised. Dependent upon the heating technique and metals involved, the stresses of hot work can affect both small and large areas, weakening the equipment later in its service life.

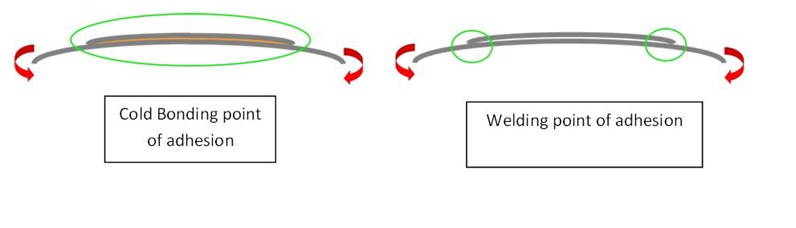

Moreover, a large number of welded patches and brackets will have cavities present. These voids simply represent areas of exposed metalwork, which can lead to the beginning of corrosion complications; displaying initially as pitting, but potentially leading to through-wall defects. Overall, the weld creates limited contact with the metal work, potentially causing the stresses placed upon the weld/repair to focus on a limited area. This increases the likelihood of stress cracking due to uneven expansion and contraction of the substrate.

In order to avoid these problems, cold bonding using a polymeric paste or fluid type material is becoming more commonplace. Significantly, this technique effectively eliminates hot work and the associated hazards. When you take into consideration the health and safety regulations currently in place, where safety is paramount, then the reduction of dangerous work processes will always be a good thing. Not only this, but the repair method is relatively simple.

Exploring cold bonding

Cold bonding can be performed with either paste or fluid grade polymer based materials, which demonstrate high adhesion and compressive strength properties. The paste grade bonding method involves surface preparation to give a rough profile. Both mating surfaces of the component and the original substrate are “wet-out” with the chosen product, and a larger layer is built up to a peak in the centre of the component. When pressed in to place, this will cause the product to force outwards, taking with it any air trapped underneath.

Use of a fluid grade follows very similar methodology. A dam can be created using a sealant and the fluid grade material is injected, either by hand or mechanical means, into the void. This method is especially useful when it is necessary to cover a large area. Multiple entry ports can be used simultaneously to provide a wide coverage of the surface, whilst also taking up complex geometries on the surface (such as damage due to pitting). A minimum of two ports are required, one for the product to flow through and the other for air to escape.

Significantly, compared to welding, cold bonding offers a layer of protection between the substrate and the repair material. Separating the metal in this instance eliminates the potential for bi-metallic corrosion due to the corrosion resistant materials used. Coverage over the repair area in these cases will be 100%, ensuring no gaps or voids are left behind. This contact makes certain that there is no room for corrosion to begin whilst also spreading any loading across the entire surface area. In turn, this facilitates high adhesion, which when coupled with a high compressive strength, means repairs are often considered equal to that of a heat based repair in process terms of service life and strength.

Finding the balance between hot and cold

Techniques involving hot work, such as welding, have been around for a long time and will always play a part in keeping the world’s industrial sector running. However, maintenance and construction welding requirements that would historically involve hot work can be completed with the use of polymeric cold bonding composites, applied and cured at ambient temperatures. As laboratory testing and field experience have shown, polymeric cold bonding composites can be applied for the repair of metallic equipment, as well as for new build applications. Notably, both methods have their respective advantages, yet these new techniques and methods are definitely offering clients much more choice in terms of how repairs are carried out.

Henry Smith

Senior Technical Service Engineer

Belzona Polymerics Ltd